Sign up for our new HTML5 workshop series and leave your competitors behind, stranded on a dessert island of outdated code.

As much as it pains me to say it, Dessert Island isn’t real. It isn’t a magical utopia of ice creams, cakes, and chocolates. It was a spelling mistake in a marketing email I received last year—a cruel, teasing extra letter inserted into a throwaway sentence that further ruined an already bad Thursday afternoon.

It doesn’t matter how great your web app is or how helpful your HTML5 workshop series will be if your marketing copy makes potential users cringe, laugh, and/or pity you. Best case scenario: They close that browser tab or delete your email. Worst case scenario: They write an article about spelling and grammar that publicly lampoons your embarrassing mistake.

Whether you like it or not, a clearly written and easily understood project plan will have a huge advantage over another plan pockmarked with spelling mistakes, comma splices, and colons where there should be semicolons. The same goes for web copy, emails to your boss, and cover letters for new jobs after your boss fires you for hiring three Eunuch Coders instead of three Unix Coders.

It doesn’t matter what your role is—developer, project manager, graphic designer, director, CEO. We all need to be able to communicate clearly and correctly.

The good news is that Coax magazine is here to help you navigate the metaphorical minefield of Oxford commas, apostrophes, whos, whoms, semicolons (a colon with a tail), homophones (words that sound the same but are spelled differently), and antecedents (don’t worry about it).

You see, Dessert Island is more than just a spelling mistake. It’s a glimpse into a reckless, dangerous world where spelling and grammar don’t matter. It’s a mirage luring you into an arid, sandy wasteland of ignorance and embarrassment and confusion.

Forget Dessert Island. Come travel to a lush world of clear, concise writing—a land with fewer mistakes, less confusion, and a solid understanding of when to use the word fewer and when to use the word less.

Word choice

Mark Twain famously said: “Action speaks louder than words but not nearly as often.” The things you write, tweet, and email will linger and lurk long after you type them out. If you misspeak in a meeting, most people will probably forget about your gaffe in a matter of minutes. However, an email in which you misspelled desert will not only reach a much larger audience, it will also remain online and in email inboxes for weeks or even months.

“But it’s just a simple email,” some people may say. “One wrong word can’t make that much of a difference. And one extra letter? Gimme a break!”

Sure. I can understand how some people would think that way. And I can understand how some people would rather cuddle than have sex. However, I would rather cuddle then have sex.

See? One letter can make a difference.

Their, there, they’re

Let’s start off with an easy one. One of the most common mistakes editors have to fix is the misuse of the words their, there, and they’re. These are called homophones—words that are pronounced the same but have different meanings and/or spellings. Here’s how to tell these three apart.

There

The word there is good friends with the word here; they are both used in relation to place or location. In the first example below, the word there denotes a specific place—the spot Brad has to stand as punishment for spelling desert incorrectly. There can also be used to denote that something exists as in the sentence, “There is too much butter on those trays.”

Examples

“Brad, please go stand over there and think about what you’ve done.”

“There are now 20 fewer subscribers on our mailing list because of Brad’s mistake.”

Their

Their is used to indicate possession in the same way we use words like our, my, or hers. It indicates that something belongs to someone or something else.

Examples

“Please take the Germans to their rooms. And don’t mention the war.

“Their email marketing campaigns don’t look as nice but at least the words are spelled correctly.”

They’re

They’re is a contraction (a shortened version) of the words they are. In this case, the apostrophe takes the place of the a in are and the two words are merged into one. Consider yourself forbidden from using they’re in any other situation.

Examples

“They’re laughing at that email Brad sent yesterday.”

“It’s only because of their stupidity that they’re able to be so sure of themselves.”

Then vs than

Here are two more homophones that trip people up. You may remember them from my clever example at the beginning of this section. The difference between these two is small but significant.

Then

Then (with an e) is most often an adverb that indicates relations in time. It’s used when one thing happens before or after another as in the sentence: “Brad sent that terrible email last week, then he was fired.” There are also other, less common uses for the word then. Sometimes, it can be a noun meaning “that time” or an adjective meaning “at that time” depending on the sentence.

Examples

“I watched two episodes of Fawlty Towers then I went to bed.” (Relations in time)

“We needed to have a meeting but then was not a good time.” (That time)

“Our then boss always proofread Brad’s emails.” (At that time)

Than

Than (with an a) is a conjunction used most often in comparisons—when one thing is bigger, smarter, earlier, or more Swiss than another thing.

Examples

“My email copy is better than Brad’s email copy.”

“There is more butter on this tray than on that tray.”

When in doubt, just remember this phrase: then rhymes with when and indicates time; than rhymes with bran and...well...I’ve got nothing.

“Superman does good. You’re doin’ well. You need to study your grammar, son.”

Who or whom?

Contrary to popular belief, the word whom is not just a fancy version of the word who. It’s sad. I know. Here’s the cold, hard truth. The difference between who and whom is the same (and just as easy to understand) as the difference between he and him or she and her.

Who

The word who is used when referring to the subject of a sentence as in the question: “Who sent that terrible marketing email out?” In this example, the subject is the person/thing doing the action (sending a terrible marketing email).

Whom

Whom is used when referring to the object of a sentence as in the question: “To whom did you send that terrible marketing email?” The object is the person/thing something is being done to (being sent a terrible marketing email).

Here’s a simple trick that will help you remember which word to use. Take the question or sentence and answer it in your head using either he or him. If the answer uses the word he (e.g. “He sent the email”) then who is the correct choice. If the answer uses the word him (e.g. “I sent it to him”) then whom is the correct choice.

And (for those of you wondering), yes—this unfortunately means the title of the 2014 YG banger Who Do You Love ft. Drake is grammatically incorrect.

If this isn’t quite clear enough and/or if you’re the type of person that needs cute and inappropriate cartoons to help grammar lessons sink in, check out the Oatmeal’s visual and in-depth exploration of who vs whom.

Which vs who vs that

The longer and more complex your sentences are, the more likely they are to confuse your readers. In such cases, words like that, which, and who are often the culprit. In the following examples, these words are relative pronouns. That’s a fancy way of saying they are used to connect information (a phrase or a clause in your sentence) to another part of your sentence (usually a noun such as “guitar” or pronoun like “he” or “whoever”). If you accidentally use one of these relative pronouns to refer the reader to the wrong word, your writing will make less sense than a kitten in a wine glass. Let’s break it down.

Which

Which is used when describing or referring to things (like guitars or emails) in your sentences so long as that description could be removed without altering the meaning of the sentence. This is called a nonrestrictive clause—essentially just extra, non-essential information. In the examples, removing the clauses that start with the word which doesn’t impact the meaning of the sentence.

Examples

“My guitar, which was stolen by some dirtbag the night my band opened for Stars, was a Fender telecaster.”

“Taco salads are a versatile and customizable meal option, which is why I love them.”

That

That can be used for either things or people but is less formal than who or which. We usually use the word that when introducing a restrictive clause. A restrictive clause contains essential information about the noun preceding it; it restricts some other part of the sentence and can’t be removed without changing the meaning.

You should try to avoid using the word that when introducing a nonrestrictive clause. It confuses people—especially British people.

Examples

“I hate the dirtbag that stole my guitar.”

“Taco salads that use Doritos instead of tortilla chips are the best.”

Who

Who is used when referring to people or a person mentioned in your sentences. Who can be used in both restrictive and nonrestrictive clauses.

Examples

“The man who stole my guitar is a huge dirtbag.”

“Firefighters had to rescue a man who was trapped in a garbage chute.”

“Brad is just a normal guy who sucks at his job.”

Does that make sense? Good. If you’re feeling keen (or are reading this at work and want to kill more time), go ahead and try out this quiz, which looks like it was created in 2001.

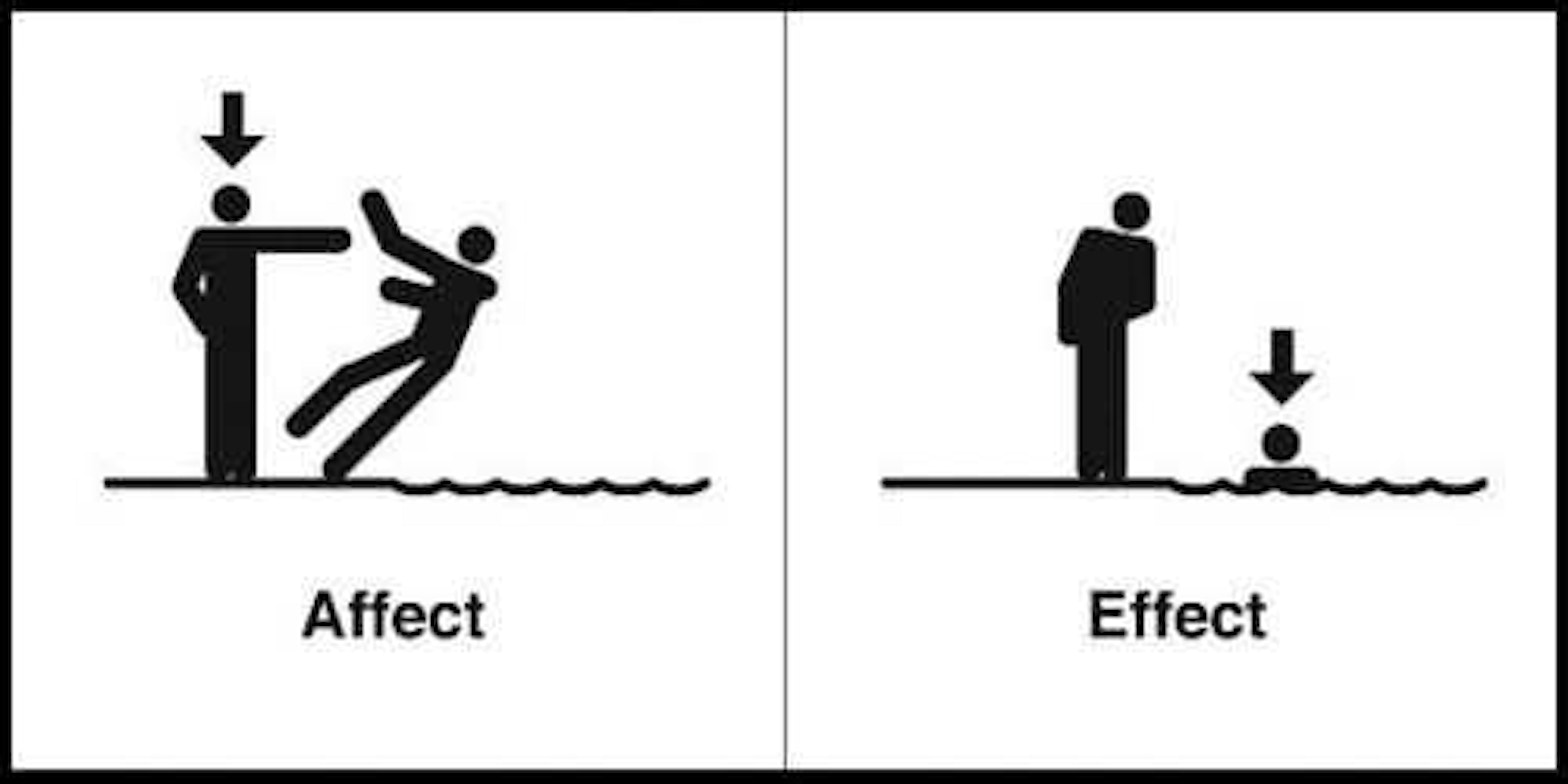

Affect vs Effect

Raise your hand if these two words confuse you. Don’t worry. You’re not alone. First off, I am contractually obligated to inform you that, while they may sound the same to many people, these two words are not actually homophones. Effect rhymes with defect; it has an “E” sound [EE-fekt]. Affect is pronounced with a “U” sound [UH-fekt] unless you are a fancy British person, in which case you will probably pronounce it with an “A” sound [AH-fekt]. Make sense? Good. Moving on.

Effect

Effect is most often a noun. It has many different (but related) definitions but can generally be understood to mean the result or outcome of something. If you need a trick to help you remember which is which, just recite the phrase “cause and effect” to yourself over and over in a hushed voice as you walk down the street. It will help your grammar and you might make some new friends!

Examples

“The lake water had a definite effect on Brad’s terrible perm.”

“This article is having a positive effect on your writing skills.”

“The theft of my favourite guitar has had a lasting effect on my ability to trust dirtbags.”

Affect

Affect is a verb—an action word. It means to influence or make a difference to something or someone as in the sentence: “Getting shoved into a lake will affect your perm.”

Examples

“That terrible email affected Brad’s job prospects.”

“Using homemade salsa will affect the flavour of your taco salad.”

Like the guy who pushed Brad into the lake, the words effect and affect are both jerks. They have some other meanings that are less common and even more confusing. Occasionally the word effect can be used as a verb meaning to produce, bring about, or to cause as in the sentence: “The Brad Is An Idiot committee was unable to effect any change in the company’s hiring process.” If you’re feeling brave, you can delve into the depths of this article to learn all the other meanings and use cases.

And please don’t feel bad if you had to read this section twice or if, even after reading it twice, you still get this one wrong from time to time. Affect and effect are totes confusing. In fact, people struggle with the difference between these two so much that some have started using the word impact as a verb instead of simply learning which is correct (e.g., “The report will surely impact the board’s decision”). DO NOT DO THIS. Lazy, weak people do this. Impact is a noun. It will always be a noun. If you don’t believe me, just ask Téa Leoni, Elijah Wood, or Morgan-goddamn-Freeman. They’ll set you straight in 121 action-packed minutes.

Fewer vs Less

Oh man. I’ve seen people get into arguments over these two. Usually, it’s just grad students with nothing better to do. Grad students are the worst. If you ever get into an argument with a grad student over this one, here is how you can put them in their place.

Less

You should use the word less when you are talking about things that don’t have a plural and/or things that can’t be counted such as rain, air, music, or salad.

Examples

“Phoenix gets less rain than Seattle.”

“Brad has less joy in his life than most people.”

“I eat less taco salad when I’m watching an amazing movie like Deep Impact.”

We also use the word less when it comes to things like time, money, and distance—things that have to do with measurement. Yes, we could count 3 hours or $100, but our dumb monkey brains understand those things as whole, singular amounts when talking about them.

Examples

“I will eat both of these taco salads in 20 minutes or less.”

“Brad, the idiot, lives less than a mile from work but still drives his car every goddamn day.”

Fewer

Fewer is the word to use when you are talking about people or things in the plural such as coworkers, ’90s movies, grad students, or tacos. My favourite trick is to remember that fewer is for things I can count. Since I can count all the mistakes in Brad’s emails, I use the word fewer when talking about them.

Examples

“The world needs fewer grad students.”

“I wish Brad’s emails had fewer mistakes.”

“Four fewer fingernails to clean.”

At this point, some of you may be thinking to yourselves: Wait, so that means that the sign at the supermarket should say 8 Items or Fewer, shouldn’t it? I know a few grad students that claim to know the answer. I can put you in touch with them. Or you can bring it up with your grocery store manager the next time you are buying eight taco salads. Your call.

Alright. Let’s recap what we’ve covered so far: Fawlty Towers is great. Brad is an idiot. Drake. Téa Leoni. Grad students are the worst. Taco salad.

Lost in translation

Words are free. But how you use them may LITERALLY cost you. Some things, like exclamation points, are straightforward to use (for most people). But a simple, misplaced comma could cause a poignant turn of phrase, your most clever marketing slogan, or an invitation to the party of the century to decay and devolve into nothing more than fodder for half-assed office cooler jokes.

Now that you better understand how to choose the right words, you need to make sure that you put them in the right order and surround them with the correct punctuation.

Sections

“The way I’m talking right now? I’d put exclamation points at the ends of all of these sentences! On this one! And on that one!”

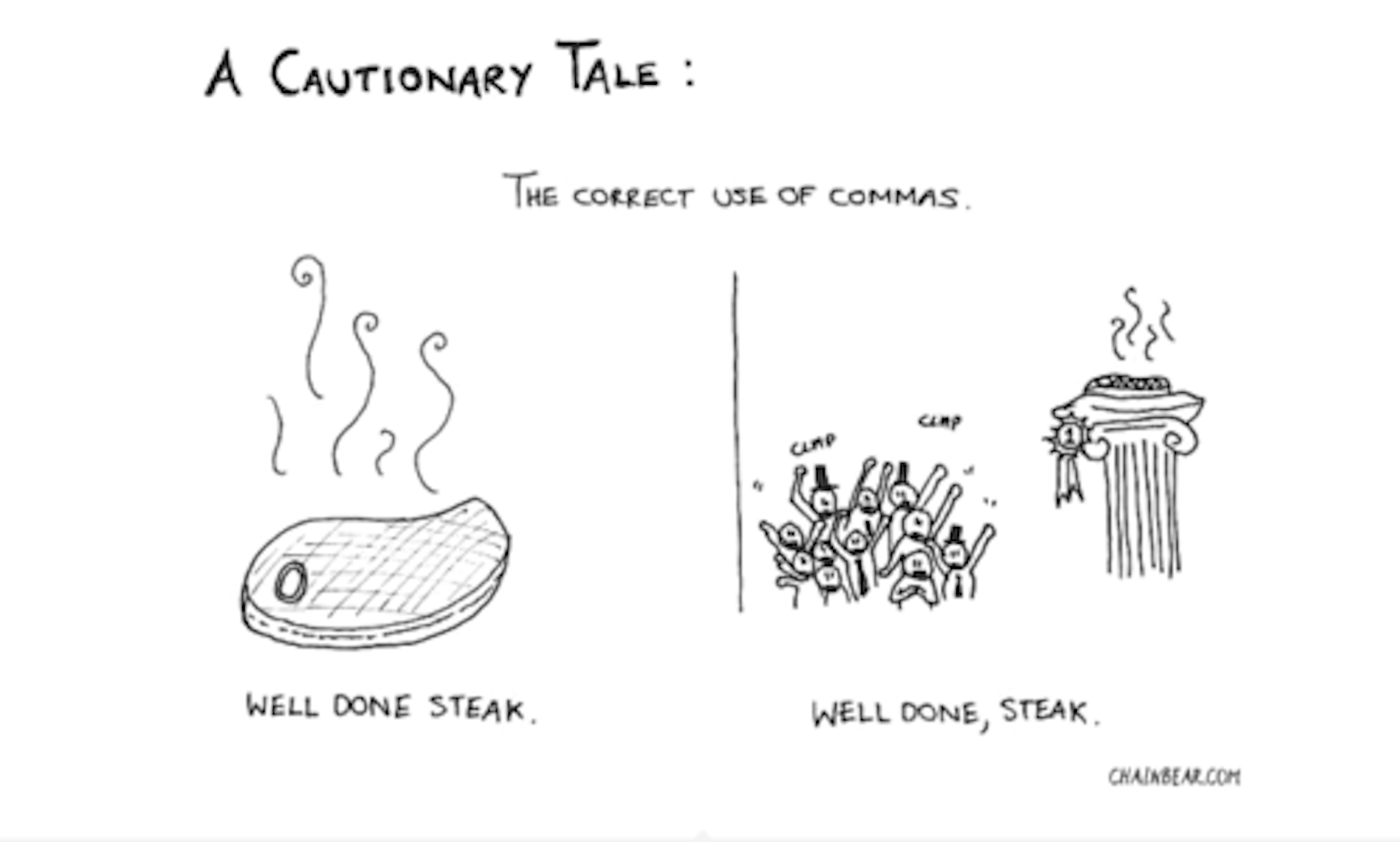

Commas

This may come as a shock to many people, but you can’t just put a comma wherever you want to. Just like you and I and Brad (at least for now), commas have specific jobs—they serve a purpose. Don’t believe me? Let’s compare two sentences.

- In my free time, I enjoy cooking my pets and watching TV.

- In my free time, I enjoy cooking, my pets, and watching TV.

Imagine that these were the bio lines of two different online dating profiles. Who would you pick? One of those people is a goddamn monster. The other is most likely normal (but probably not doing enough to set him or herself apart in the online dating world).

One misplaced comma could be the difference between a lifetime of happiness and the world’s worst first date. Now that you understand what’s at stake, let’s take a closer look at where and where not to use a comma.

Commas in a series

The above examples showcase one of the main purposes of the comma: separating elements in a series. In other words, commas are used when listing things in a row—things like personal interests, languages you are fluent in, or favourite colours.

(While there is some disagreement about whether to place a comma between the final two items in such lists, there is, in fact, a correct answer. See the section on the Oxford or serial comma below. If your company’s style guide advises against using the Oxford comma you should probably look into changing that.)

Commas around interrupters

We also use commas around interrupters. Interrupters are words, phrases, or clauses that (you guessed it) interrupt a sentence. Commas must be placed around such interrupters as in the sentence, “Brad, to be perfectly honest, is an idiot.” In this case, the clause to be perfectly honest interrupts the otherwise complete sentence Brad is an idiot and thus requires a comma on either side of it.

Example

“The 1998 movie Deep Impact was, unfortunately, beaten at the box office by the movie Armageddon which attempts to prove that it would be easier to train oil workers to be astronauts than to train astronauts to be oil workers.”

Commas after an intro

Commas also help us by separating an introductory word or phrase. If you start a sentence with words like meanwhile, still, or however, you need to follow them with a comma. The same goes for descriptive phrases that set up or lead into your sentence and introductory dependant clauses that provide background information. You can keep an eye out for dependent clauses because they usually start with an adverb—words like although, after, before, if, since, and when.

Examples

“Unpopular and mistake-prone, Brad has become the next in line to get fired.” (Descriptive phrase)

“If he wants to keep his job, Brad needs to get his shit together.” (Dependant clause)

Commas that separate

Commas are also used to separate two different independent clauses in the same sentence. If one sentence has two phrases that could each be their own sentence, you join the two together with a comma and a coordinating conjunction—words like and, but, or, for, nor, so, and yet. Inserting a comma on its own without a coordinating conjunction is called a comma splice and will bring shame to your family (more on comma splices below).

Examples

“Brad was surrounded by dozens of coworkers, but he had never felt more alone.”

“The producers of the 1998 movie Armageddon knew the story’s premise was completely absurd, so they tried to distract and appease moviegoers with Liv Tyler and a top-40 ballad by her father’s band Aerosmith.”

Commas that coordinate

Another common situation where you will need to use a comma is when you are linking coordinate adjectives—two words of similar importance that are used together to describe the same noun. Slippery and dangerous pretty much mean the same thing when used to describe a road. They explain and modify the road’s condition. So, when you put them side by side without the word and, you need to use a comma.

Adjectives that describe the noun in different ways do not need a comma—these adjectives cumulate rather than coordinate. If I say “I ate a giant blueberry muffin for breakfast,” the word blueberry describes the type of muffin I ate but the word giant describes the size of that blueberry muffin.

Examples

“Slippery, dangerous roads are common in northern Canada.” (Coordinate adjectives)

“I just ate a superb hand-made taco salad.” (Cumulative adjectives)

If you want to go further down this rabbit hole, Grammar Girl does a good job of clarifying the difference between coordinate and cumulative adjectives. And for an extended list of comma rules and use cases (and many more examples), check out the always excellent Online Writing Lab (OWL) at Purdue University.

Comma splices

The words comma splice have been scrawled angrily across English essays since the invention of the red pen. Comma splices are a common mistake made by many well-intentioned people. The good news is that they are easy to spot and easy to fix. Let’s work through an example.

“Brad waited for a chance to sneak outside, he had been worrying about his annual review all day.”

The sentence above is an example of a comma splice or a run-on—two independent clauses joined by a sad and lonely comma. Brad waited for a chance to sneak outside is the first independent clause. He had been worrying about his annual review all day is the second. Each could be its own sentence but they are held together (poorly) as one sentence by that misused comma.

Don’t worry. Just like the example sentence above, each and every comma splice can easily be fixed in one of four ways:

1. Make two sentences.

So easy. Replace the comma will a period and capitalize the first letter following. All better.

Example

“Brad waited for a chance to sneak outside. He had been worrying about his annual review all day.”

2. Add a coordinating conjunction.

You have already learned about these. Adding a coordinating conjunction after the comma will fix everything.

Example

“Brad waited for a chance to sneak outside, for he had been worrying about his annual review all day.”

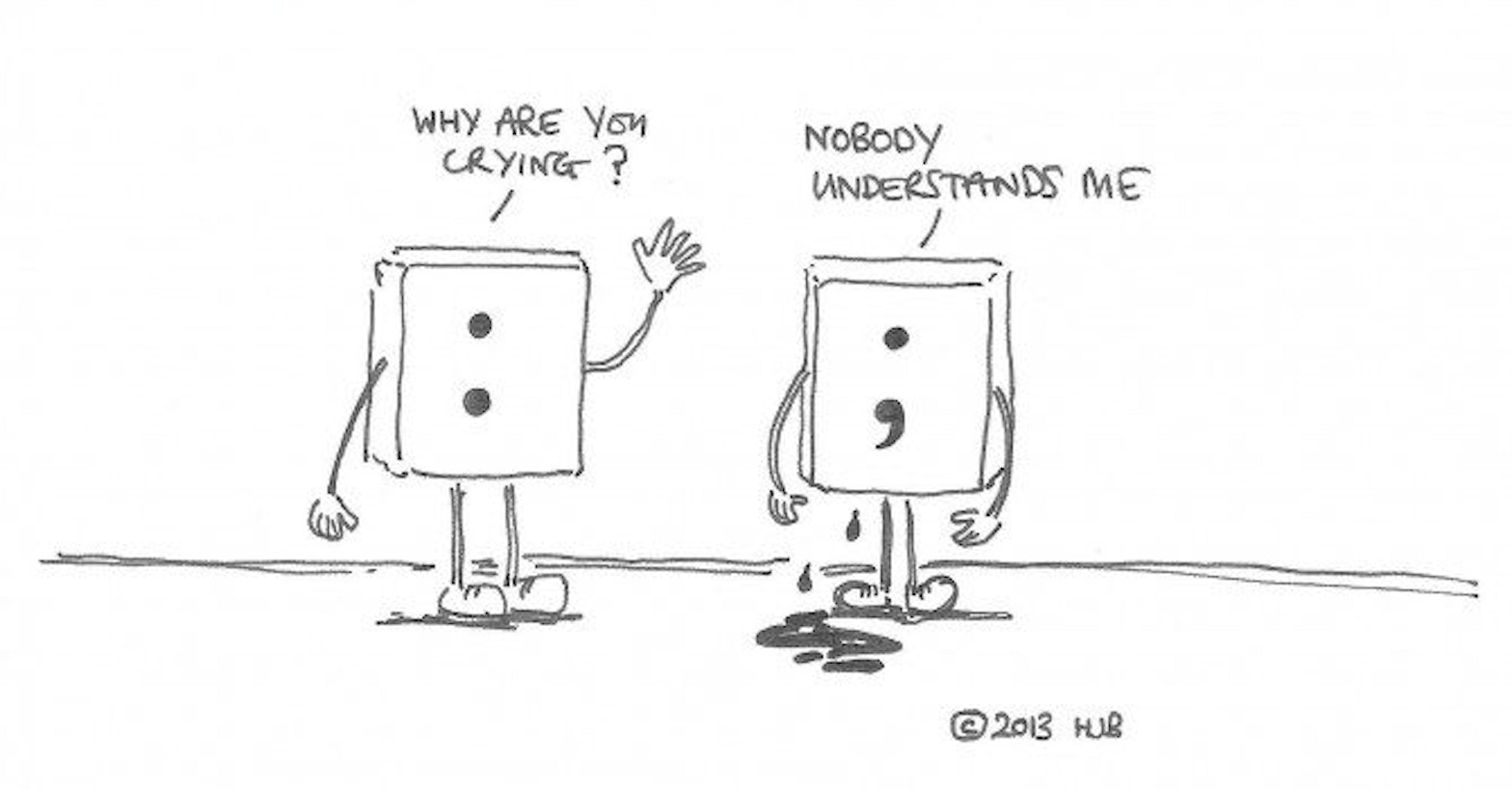

3. Upgrade the comma to a semicolon.

Semicolons scare people and are often misused. However, they are a useful little piece of punctuation as strong and mighty as the period. A perfectly acceptable use of the semicolon is to connect two related sentences.

Example

“Brad waited for a chance to sneak outside; he had been worrying about his annual review all day.”

4. Subordination.

Sounds sexy, doesn’t it? You can also fix a comma splice by altering one of the sentences so that it depends on the other. All you have to do is replace the comma with a subordinate conjunction like because, until, before, unless,while, or after.

Example

“Brad waited for a chance to sneak outside because he had been worrying about his annual review all day.”

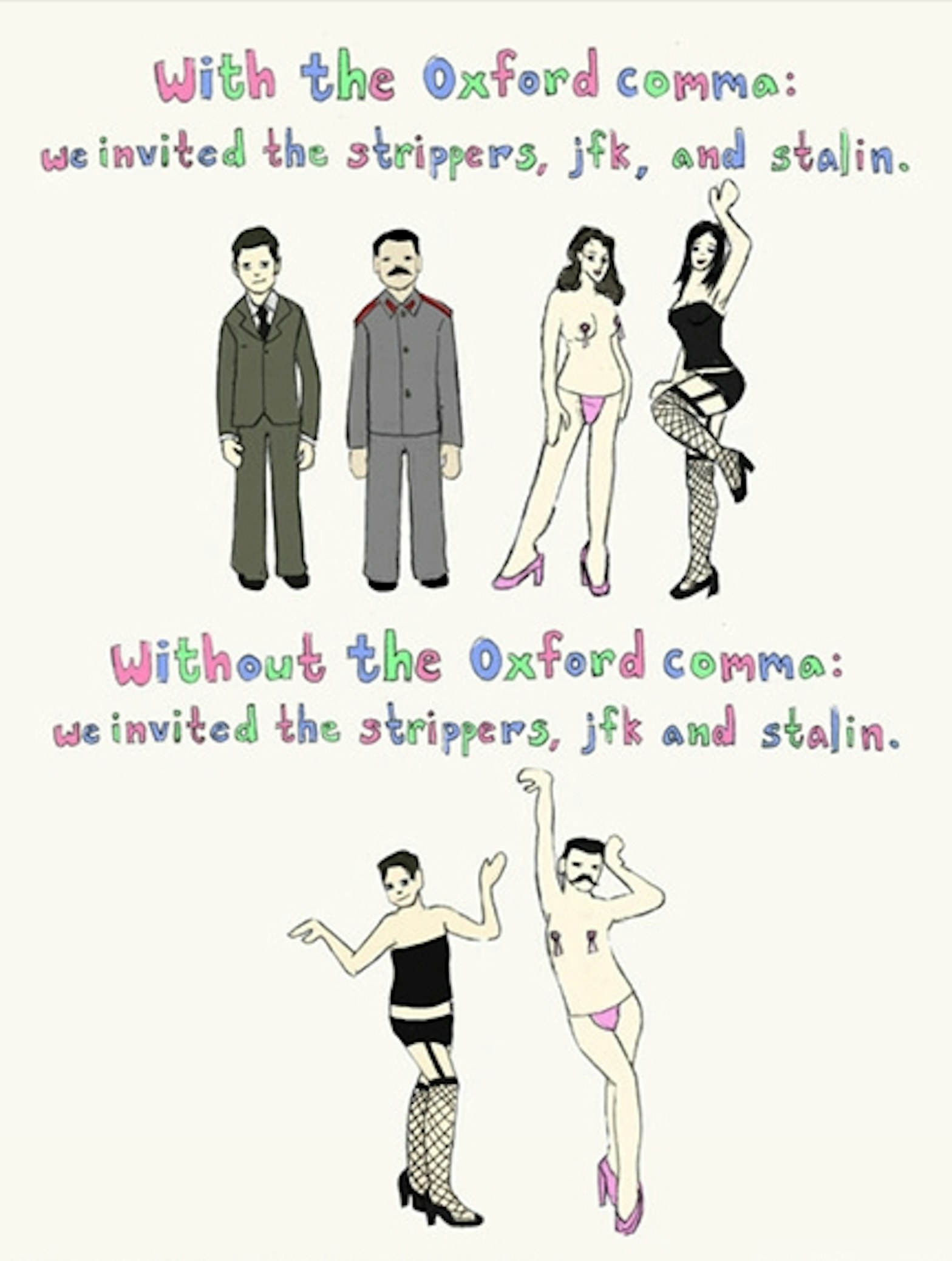

Oxford or serial comma

I can’t talk this much about commas without addressing the Oxford (or serial) comma—the comma used after the second-to-last item in a list. Some people insist on using a comma in such lists. Others refuse to do so. These reckless monsters leave the word and all alone at the end of their lists like this: “When I was young, I looked up to my parents, Superman and Wayne Gretzky.”

Some things, like the use of italics or the Oxford comma or ellipses, will be defined and mapped out by the style guide of your company, magazine, or internet startup. However, any style guide that suggests not using the Oxford comma is probably due for an update.

Sure, the Oxford comma is not always necessary. I understand. But in the many cases where it is necessary, omitting the Oxford comma makes you look like an ass.

Anyone who disagrees with this point is either beholden to one of those outdated and ill-informed style guides or is a graduate student who truly believes that I was raised by Superman and Wayne Gretzky—a fictional, overrated superhero and a Canadian hockey legend.

The Oxford comma is the real superhero here. And, after reading this article, if any of you feel compelled to update your company’s style guide let us know—we would love to help you refresh or create your very own style manual.

Em-dashes, en-dashes, and hyphens

Hyphens

Hyphens (the shortest of the three) are most often used to join compound adjectives such as self-evident, second-worst, long-term, man-eating, or (ironically) non-hyphenated. They also separate syllables of a word split across a line break and, unsurprisingly, in hyphenated names such as Olivia Newton-John or Courtney Cox-Arquette (the second-worst Friends character).

Examples

“The space drill in Armageddon used a state-of-the-art design.”

“According to Roger Ebert, most of the dialogue in Armageddon is either shouted one-liners or romantic drivel.”

En-dash

The en-dash is the middle child and thus the most overlooked and misused of the three. When used correctly, the en-dash most often connects related values or a range of values. It stands in for the word to in such cases.

Examples

“World War II, in which Switzerland and all of its statues remained neutral, lasted from 1939–1945.”

“The Cleveland Browns beat the Dallas Cowboys 45–14 but nobody cares because American football is boring.”

“Brad’s annual review is tomorrow from 3:30–4:15.”

Em-dash

The em-dash is the longest and most graceful of the three lines. As such, it is also the most versatile. The em-dash is often used to stylistically replace a comma, colon, or parentheses when separating a phrase or word for extra emphasis, contrast, or explanation. It is usually used without spaces—like its siblings, it needs to touch the words on either side of it.

Examples

“After three weeks on set, the cast of Armageddon was confused by the direction of the film—or rather, the lack of direction.”

“Upon discovering Brad’s other mistakes—all 245 of them—the review panel suggested relocating Brad to the mailroom.”

If you’re a regular reader of Coax and like the way we do things, check out the Coax Magazine style guide—it has a great section on where and how to use these (and many other) tricky bits of punctuation.

Apostrophes

The apostrophe is a good friend of the comma—a fancy well-to-do friend from uptown. They look similar but hang out in different places and behave differently. While the comma enjoys slumming it down on the baseline near the feet of your typed words, the apostrophe hangs out up at the median at the top end of the letters in your sentences.

The apostrophe is used for one of two reasons: to indicate possession or to show that certain letters are missing in a contraction.

Possession (not the demonic kind)

When something belongs to someone or something else, we use an apostrophe to indicate possession as in the sentence: “Brad’s career is in jeopardy.” This indicates that the career we are talking about belongs to Brad. Sometimes proper nouns (such as Switzerland or Friday) act as if they own something and, even though it may not make sense, it is generally accepted that such examples follow the same rules.

Examples

“Superman and Wayne Gretzky are taking me to Friday’s hockey game.”

“Hands down, Switzerland’s greatest artistic contribution to the world is a statue of a man eating a sack of babies.”

Don’t forget to watch out for plural possessives. If the object belongs to a group of things or people, most people add an apostrophe without an extra letter S as in the sentence: “The soldiers’ guns were all jammed with peanut butter.” In this case, the apostrophe indicates that the guns belong to the soldiers (but why they were all jammed with peanut butter remains a mystery). For more detailed and illustrated rules about apostrophe use, check out The Oatmeal.

Contractions (not the pregnancy kind)

A contraction is when you omit a few letters to shorten a word or to combine two words. In either case, you use an apostrophe to indicate that letters have been omitted in words like don’t (do not), it’s (it is), and wouldn’t (would not).

Important note

The only time you can use the contraction it’s with an apostrophe is in place of the words it is. When the word its is indicating possession it doesn’t get an apostrophe.

Example

“Switzerland is known for its watches, its chocolate, its neutrality, and its amazing statue of a man eating a sack of babies.”

Some of you may be tempted to include an apostrophe with plural words. RESIST THIS URGE! Plural words on their own (such as cats or guns or taco salads) do not need apostrophes—please stop putting them there. If any of you feel such temptations, you have likely been possessed by the ghost of a grad school dropout and you will need to immediately perform an exorcism by finding the unfinished copy of the ghost’s Ph.D. Thesis which is probably titled something like, Fair is Fare is Faire: A Comparative Analysis of Homophones in the Works of the Brontë Sisters. Goddamn grad students.

“By the way, Y‑O-U-apostrophe-R‑E means ‘you are.’ Y‑O-U‑R means ‘your.’ ”

The colon and the semicolon

Using these two pieces of punctuation incorrectly is a sure-fire way to embarrass yourself. You may not have to use them in your communications, but if you do (or want to), you’ll need to know how to use them and which to select in different situations.

Semicolon

A semicolon (a dot and a comma—this one ;) separates things. Most often, a semicolon separates two independent clauses that could each be their own sentence but are closely related to one another.

Examples

“It was well below zero; the roads were treacherous.”

“I like to make jokes about Switzerland; however, it is a beautiful country well-worth visiting.”

“Using a semicolon isn’t hard; I once saw a party gorilla do it.”

Colon

The colon (two dots—this one :) combines things. It introduces something new to the sentence. Most often, this is a list of items, but a colon can also introduce a definition, an exclamation, a statement, or related information.

Examples

“I know exactly what you’re thinking: you want more weird facts about Switzerland.”

“Fine. Switzerland has enough nuclear fallout shelters to house its entire population: a little over 8 million people.”

“To make a good taco salad you must be sure to include a few key ingredients: homemade salsa, black beans, crisp lettuce, and Doritos (instead of tortilla chips).”

E.G. & I.E.

If, at the end of the day, you take away only one thing from this long, entertaining, and incredibly helpful article, please let it be this: the abbreviations e.g. and i.e. are not interchangeable. Using one when you should use the other is like writing dessert when you mean to write desert. Both e.g. and i.e. are abbreviations for latin phrases but each has a specific meaning.

E.G.

As you probably know, e.g. (latin for exempli gratia) means for example—it provides additional options. You use e.g. when you are providing an example or examples of something previously stated. If you are unsure whether to use e.g. in your sentence, say the words “for example” aloud in its place and see if the sentence still makes sense.

Examples

“There are many ways for a copywriter to get fired (e.g., misspelling the word desert in a marketing email to 30,000 subscribers).”

“I know many obscure facts about Switzerland (e.g., It is illegal to keep just one guinea pig; Swiss people can only own guinea pigs in pairs).”I.E.

As you may not know, i.e. (latin for id est) means that is or in other words—it narrows things down. You use i.e. when you are elaborating on something previously stated and/or providing additional explanation or clarification. If it helps, say the sentence aloud replacing “in other words” for the i.e. and see if the sentence still makes sense.

Examples

“In Switzerland, the service charge is included in most prices (i.e., you don’t have to leave a tip).”

“There is also a giant three-legged chair sculpture in Geneva symbolizing and raising awareness about ICBL (i.e., the International Campaign to Ban Landmines).”

Finally, for both cases, most self-respecting humans (and those of us at Coax) put a period after each letter and a comma after the second period as we have done in the above examples. Europeans tend to omit the periods. But they also tend to make baby-eating statues, so I’d be hesitant to follow their lead on this one.

Clear and simple

Oh man. Do you feel smarter yet? You should. You look smarter. At least I think so.

This final section is less about rules and more about best practices. Different writers write differently. That’s what makes writing and reading so wonderful—the diversity of voices. I encourage you to find your own style and your own voice.

If you’ve struggled to get through this article, if my writing style feels like sandpaper dragged across your eyeballs, that’s fine. Don’t bother with this last section. There are plenty of other writers offering tips and guides and rules that you may find more palatable. You can follow George Orwell’s rules for writing. If you want a more evocative and philosophical guide, you can adhere to Nietzsche’s guidelines for writing. You can listen to Stephen King or Margaret Atwood or Tom Clancy (in which case your writing will be less clear and simple and more clear and present and in danger).

However, if you’ve made it this far (and/or have another 5 minutes to kill before your next meeting), here are some final suggestions from your friendly neighbourhood magazine editor about active voice, adverbs, and making sure your nouns and verbs get along with one another.

Active voice

You may have heard your editor or copywriter or landlord talking about active and passive voice. They may have even asked you to use less passive voice in your writing—especially if your name is Brad.

Put simply, using active voice means that the subject of the sentence is actively performing the action described by the verb in the sentence. Passive voice means the subject passively receives the action of the verb—the action is being done to them.

Examples

“Brad sends terrible emails.” (Active voice)

“Terrible emails are sent by Brad.” (Passive voice)

There are a few situations in which passive voice makes sense and is even preferable. Unfortunately, many upstanding, respectable people use passive voice elsewhere even though studies suggest that it is harder for people to understand. News outlets and (ugh) grad students use passive voice all the time in their confusing, awkward, or wordy sentences. Politicians often revert to passive voice to distance themselves from mistakes or gaffes because passive voice obscures the relationship between the subject (the politician) and verb (the thing they did). Passive voice conceals identity and shirks responsibility like an airline acting blameless after losing your luggage.

Examples

“I made a mistake.” (Active voice)

“Mistakes were made.” (Passive voice)

“We lost your luggage.” (Active voice)

“Your luggage appears to have been lost.” (Passive voice)

Active voice lends itself to stronger, more clear and concise writing. It makes you easier to understand. It creates a more assertive and positive tone. Don’t be a skeezy politician. Rise above the graduate students. Use the active voice.

If you want some help converting passive voice to active voice in your own writing, the OWL at Purdue has a superb article on that very topic.

Dangling modifiers

A dangling modifier is a word or phrase that fails to modify what it was supposed to. Sometimes, fancy people call these dangling participles. Other times, less fancy people call them floaters. Sometimes the dangling modifier is a word that doesn’t even appear in the sentence.

Example

“Having seen Armageddon, Deep Impact is more entertaining.”

The example above implies that the movie Deep Impact has seen the movie Armageddon. That’s absurd. The phrase, Having seen Armageddon, is trying to modify a subject that isn’t there—most likely a person like you or I or Brad. A correct version of this sentence would require something or someone that has actually (and unfortunately) seen Armageddon.

Example

“Having seen Armageddon, I can assure you Deep Impact is more entertaining.”

Here’s another dangling modifier we can fix:

“Professional and detail-oriented, Brad’s work ethic is inspiring.”

This sentence is both grammatically incorrect and factually incorrect. First off, as I have made very clear, Brad is the opposite of detail-oriented. And while Brad could potentially (in some other dimension) be professional and detail-oriented, he is not the subject of the sentence—his work ethic is. In this case, the phrase Professional and detail-oriented is the dangling modifier because it’s meant to modify or describe Brad but mistakenly describes Brad’s work ethic. A grammatically correct version of this sentence would have Brad as the subject.

Examples

“Professional and detail-oriented, Brad has an inspiring work ethic.” (Grammatically correct)

“Inept and careless, Brad has an underwhelming work ethic.” (Grammatically and factually correct)

If you find your modifiers dangling from time to time, don’t worry. There are a few easy ways to fix them.

First, make sure the thing you are referring to actually appears in the main clause of the sentence and is the subject of that clause. You can also move the dangling modifier into the main clause (e.g., “Brad is inept and careless and has an underwhelming work ethic”) or you can make the dangling modifier its own introductory clause (e.g., “Because I have seen both Armageddon and Deep Impact, I can assure you that the latter is more entertaining”).

“ ‘Sentence fragment’ is also a sentence fragment.”

Subject-verb agreement

Subjects and verbs need to get along if you want your writing to make sense. The general rule is that a singular subject (Switzerland) goes with the singular form of a verb (is great) and plural subjects (Swiss statues) go with the plural form of a verb (are great).

However, the more complex your sentences get, the easier it is to lose track of the relationship between the subjects and their verbs. Extra phrases, pronouns, lists, and collective nouns can disguise the subject of a sentence. Here are some more examples. The correct versions of each sentence have both subjects and verbs noted in bold.

Examples

“Several short breaks during a writing assignment is more beneficial than one long rest.” (Incorrect)

“Several short breaks during a writing assignment are more beneficial than one long rest.” (Correct)

“This selection of expensive Swiss chocolates taste like heaven.” (Incorrect)

“This selection of expensive Swiss chocolates tastes like heaven.” (Correct)

“Terrible dialogue, in addition to an absurd premise and questionable casting choices, make Armageddon a joke of a movie.” (Incorrect)

“Terrible dialogue, in addition to an absurd premise and questionable casting choices, makes Armageddon a joke of a movie.” (Correct)

If you want to understand the rules and reasons behind these examples, this site lists almost all of them.

Trim the fat

I mean that metaphorically of course. In many of the above examples, complex and wordy sentences caused the grammatical mistakes. An easy way to prevent these problems is to write shorter, simpler sentences. Here three easy ways to trim the fat in your writing.

Cut it out

Say more with less. If you can cut out a word, do it. Long, complex, and involved sentences don’t make you sound smart. Some people may disagree with that claim, but those people are most likely grad students and they are wrong. Web apps like Hemingway can help you identify long and complicated sentences that need to be addressed.

Examples

“If a man does not keep pace with his companions, perhaps it is because he hears a different drummer.” (Verbose)

“Some men march to a different beat.” (Concise)

“I’m going to have to let Brad go due to the fact that he keeps making the same mistakes.” (Ugh)

“I’m firing Brad because he keeps making the same mistakes.” (Finally)

Kill the adverbs

Adverbs are unnecessary words that are added to a sentence to modify a verb. They are for lazy, boring people like Brad or whichever film executive green-lit Armageddon. Using adverbs is like adding chicken to a caesar salad. It doesn’t make the bad salad any better. It just makes a bad salad more expensive. Don’t add an extra word to make your lazy verb more exciting. Just choose a better verb in the first place.

Examples

“Brad listened closely to Ben Affleck’s terrible dialogue.” (Lazy)

“Brad absorbed Ben Affleck’s terrible dialogue.” (Less lazy)

“The woman walked quickly out of the screening of *Armageddon*.” (Meh)

“The woman raced out of the screening of *Armageddon*.” (Obviously)

“Adverbs are a lazy tool of a weak mind.”

Prepositional phrases

The word of is a preposition—a word used to indicate a relationship between a noun or pronoun and another part of your sentence. Unfortunately, prepositions like of, on, and from are often used to create unnecessarily verbose and bloated sentences.

An easy way to clean up your writing is to remove (or avoid) prepositional phrases. On a monthly basis can be replaced with monthly. The opinion of the council can be replaced with the council’s opinion. At that point in time can be replaced with then as you learned earlier.

Examples

“The point of the discussion was to agree as a group about what to do with the funds in the budget made available by Brad’s termination.” (Terrible)

“The group discussed what to do with the extra money in the budget.” (Taco salads for everyone!!!))

Don’t be Brad

Words are precious. They carry our desires, our intentions, our hopes, dreams, and written requests for days off. They allow us to describe the best versions of ourselves and they console us when we fail to live up—yes, I’m looking at you, Brad.

I hope these tips and tricks and examples strengthen your writing. I hope you are able to impress your coworkers with your new and dazzling understanding of punctuation and grammar. I hope Brad has learned his lesson.

In closing, I’ll leave you with this. Whether you are a writer or not, I encourage you to write more. Whether you follow the rules or not, I encourage you to write more. Whether you need to or not, write more. Being able to communicate your ideas is important no matter what you do or where you do it.

And if you’re going to break any of the above rules—if you insist on using the English language incorrectly—do so boldly and with intention. Do it with pride. Because in spite of everything you’ve just read, at the end of the day, they’re all just made-up words.